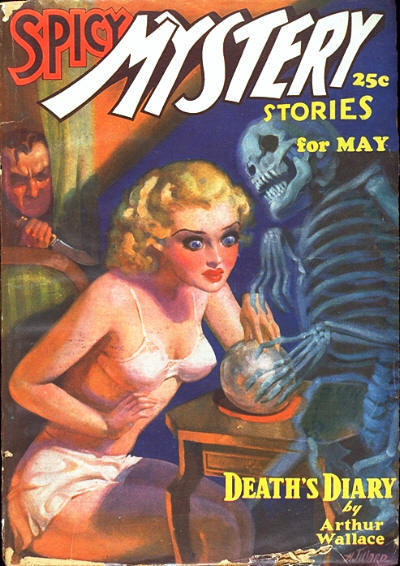

“Spicy Mystery Stories” was one of the Culture Publications pulps, and you just can’t get more ironic than that. The Spicies sold for a quarter and in most cities they resided under the counter. The cover art gave the game away. Sex, violence, and death all in one nifty semi-surrealist H.J. Ward painting. Dali should have been working for the pulps.

This issue, reprinted by Adventure House, is from May, 1936, and provides a terrific introduction to the world of weird menace storytelling. “Weird menace” is a particular subgenre of the horror story in which, generally, a gothic atmosphere is established, usually in a paragraph or two, and some sort of incredible danger is introduced. This danger will more than likely come in the form of a human monster, a zombie, a ghost, a being returned from the past, or just an all-round, slavering, lecherous, humanoid BEM. The kicker is that, as in the gothic novels that came before them and Scooby-Doo who came after, weird menace villains always turn out to be some demented-murderous-greedy yahoo who wants the mansion-fortune-beautiful gal all for himself.

This issue contains nine tales, all of which are fun. Each seems placed where it is in order to top the previous one in whacko plotting.

The first is “Death’s Diary” by Arthur Wallace, and it’s about a mad scientist who has developed a means of transferring a soul from one body to another. In a similar vein, Clint Morgan’s “Blood of a Dog” features another less than sane man of science, this one creating a fluid made from the essence of beast. Inject it into a human and the result is . . . what? In “She Who Was Dead” (nice title) by Jerome Severs Perry a beautiful, mad girl rises from the dead—or does she? Jerome Severs Perry was a popular penname for Robert Leslie Bellem, about whom more later.

Now we get to Mort Lansing’s “Green Eyes” and the plotting takes a turn toward the seriously bizarre. In this one, a mad painter (to give us a break from mad scientists) kidnaps people to contort their bodies into tableaux of torture of pain. Prospective patrons of the bloody arts wander through his gallery looking at these living mannequins of death and when they see a pose they like, they pay the artist to paint it for them. Eli Roth, I have a story you might want to take a look at.

In “Death Shows the Way,” by Tay Philips, a man escapes from an asylum to return to the place of his wife’s death only to find her three-year old corpse waiting in bed for him.

With “Cord of Cowardice,” by Cary Moran, we return to the relative normalcy of a man dressed as a medieval Viking who puts his wife’s death mask on a young woman so he can consummate his nuptials. Seems his virgin bride died before he had the chance three years ago.

In the brief “The Crowded Coffin,” by Dennis Craig, lovers pass along a disease that makes hair grow five feet a night and drains males of strength until they die. It’s Samson in reverse.

Finally we come to Robert Leslie Bellem under his real name, creator of Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective, and one of the bedrock writers of the Spicy line. In “Cavern of the Faceless,” a woman who has been scarred hideously in a beauty parlor accident (!) kills herself. Her husband then buys the place where her injury occurred despite the fact that four of the employees have disappeared. It appears that he is a mad revenger, but not only is this a weird menace story, but it’s a weird menace story by Robert Leslie Bellem. I can’t give too much away but trust me; wilder plots than this one, they just don’t write.

This issue concludes with John Bard’s “The Second Mummy,” a story about an American detective who is called by an old friend to Mexico to find a missing object d’art. This one has a nice punch in the ending.

Oh, and as for the “spicy” bits, here’s a typical passage from the Bellem story:

“With infinite tenderness, Kendrick Westfall pressed his mouth upon her parted lips. His hand stole upward along her side; his arm crept about her slim waist. As he drew her close, he could feel, through the thinness of her summery frock, that firm half-globe of sweet flesh, the ripple and play of her muscles—the tremor of her soft breast against him. His whole being ached with ecstasy at her response . . . “

We all know what those three dots at the end represent, and that’s about a titillating as it gets. The Spicies indulged in a little kinkiness, but it tended to be more underplayed than that appearing in such hard-cored weird menace titles as “Horror Stories” and “Terror Tales.”

I can’t dismiss this issue of “Spicy Mystery” by saying that the stories are silly. Of course they’re silly. Anyone over the age of 12 in 1936 knew they were silly. And the objection to that is . . . ?

This issue, reprinted by Adventure House, is from May, 1936, and provides a terrific introduction to the world of weird menace storytelling. “Weird menace” is a particular subgenre of the horror story in which, generally, a gothic atmosphere is established, usually in a paragraph or two, and some sort of incredible danger is introduced. This danger will more than likely come in the form of a human monster, a zombie, a ghost, a being returned from the past, or just an all-round, slavering, lecherous, humanoid BEM. The kicker is that, as in the gothic novels that came before them and Scooby-Doo who came after, weird menace villains always turn out to be some demented-murderous-greedy yahoo who wants the mansion-fortune-beautiful gal all for himself.

This issue contains nine tales, all of which are fun. Each seems placed where it is in order to top the previous one in whacko plotting.

The first is “Death’s Diary” by Arthur Wallace, and it’s about a mad scientist who has developed a means of transferring a soul from one body to another. In a similar vein, Clint Morgan’s “Blood of a Dog” features another less than sane man of science, this one creating a fluid made from the essence of beast. Inject it into a human and the result is . . . what? In “She Who Was Dead” (nice title) by Jerome Severs Perry a beautiful, mad girl rises from the dead—or does she? Jerome Severs Perry was a popular penname for Robert Leslie Bellem, about whom more later.

Now we get to Mort Lansing’s “Green Eyes” and the plotting takes a turn toward the seriously bizarre. In this one, a mad painter (to give us a break from mad scientists) kidnaps people to contort their bodies into tableaux of torture of pain. Prospective patrons of the bloody arts wander through his gallery looking at these living mannequins of death and when they see a pose they like, they pay the artist to paint it for them. Eli Roth, I have a story you might want to take a look at.

In “Death Shows the Way,” by Tay Philips, a man escapes from an asylum to return to the place of his wife’s death only to find her three-year old corpse waiting in bed for him.

With “Cord of Cowardice,” by Cary Moran, we return to the relative normalcy of a man dressed as a medieval Viking who puts his wife’s death mask on a young woman so he can consummate his nuptials. Seems his virgin bride died before he had the chance three years ago.

In the brief “The Crowded Coffin,” by Dennis Craig, lovers pass along a disease that makes hair grow five feet a night and drains males of strength until they die. It’s Samson in reverse.

Finally we come to Robert Leslie Bellem under his real name, creator of Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective, and one of the bedrock writers of the Spicy line. In “Cavern of the Faceless,” a woman who has been scarred hideously in a beauty parlor accident (!) kills herself. Her husband then buys the place where her injury occurred despite the fact that four of the employees have disappeared. It appears that he is a mad revenger, but not only is this a weird menace story, but it’s a weird menace story by Robert Leslie Bellem. I can’t give too much away but trust me; wilder plots than this one, they just don’t write.

This issue concludes with John Bard’s “The Second Mummy,” a story about an American detective who is called by an old friend to Mexico to find a missing object d’art. This one has a nice punch in the ending.

Oh, and as for the “spicy” bits, here’s a typical passage from the Bellem story:

“With infinite tenderness, Kendrick Westfall pressed his mouth upon her parted lips. His hand stole upward along her side; his arm crept about her slim waist. As he drew her close, he could feel, through the thinness of her summery frock, that firm half-globe of sweet flesh, the ripple and play of her muscles—the tremor of her soft breast against him. His whole being ached with ecstasy at her response . . . “

We all know what those three dots at the end represent, and that’s about a titillating as it gets. The Spicies indulged in a little kinkiness, but it tended to be more underplayed than that appearing in such hard-cored weird menace titles as “Horror Stories” and “Terror Tales.”

I can’t dismiss this issue of “Spicy Mystery” by saying that the stories are silly. Of course they’re silly. Anyone over the age of 12 in 1936 knew they were silly. And the objection to that is . . . ?

No comments:

Post a Comment